No Rivals: The Kingdom (Part IV)

Founders Fund’s power spans Silicon Valley, the Pentagon, and the White House. Can it remain singular as others mimic its moves?

“Mario provides in-depth, never-gets-old insights from leading technologists of our age and packages them in a creative, friendly format." — Alexander, a paying member

Friends,

The end is upon us.

In the final edition of “No Rivals,” we examine the full reach of Founders Fund’s power, spanning Silicon Valley, the Pentagon, and the White House. No other firm has played a larger role in tech’s rightward shift or the country’s growing techno-militarism. Those efforts have been driven by Founders Fund’s unusual (and strikingly successful) approach to incubation, a process that has yielded the $30.5 billion Anduril, space manufacturer Varda, and nuclear startup, General Matter.

We conclude with a distillation of Founders Fund’s “House Style” and an in-depth look at its performance. This includes a position-by-position analysis and represents the most detailed accounting of the firm’s returns ever reported.

If you haven’t started “No Rivals” yet, you can now read the entire series front to back:

Part IV: The Kingdom (below)

The response to this series has been overwhelming. We’ve heard from so many of you that “No Rivals” is one of your favorite works from The Generalist.

“Mario Gabriele pulls back the curtain on Founders Fund's incredible rise and why they think so differently. Add this to your weekend reading list!”

“I've been literally obsessed with the PayPal Mafia for many years now, but this deep dive into Founders Fund does feel like the cherry on top!”

“One of the best reads of this year so far. Worth the subscription.”

“Damn, this is one of the best reads of 2025”

To support our work, help us write our next great series, and unlock the complete text, become a premium member now. For just $22/month—less than a single business lunch—you’ll get access to dozens of meticulously crafted case studies, management playbooks, and tactical guides. All are designed to make you a better investor, more productive founder and operator, and more thoughtful person.

Previously on No Rivals…

Silicon Valley’s philosophical trinity consists of three prophets: Marc Andreessen, Paul Graham, and Peter Thiel. Of the three, Thiel wields the greatest influence. His once-arcane positions on democracy’s failings and American militarization have become mainstream in tech.

Thiel’s intellectual power stems from an unusual mind, defined by reflexive contrarianism and a willingness to follow thoughts into forbidden territories.

With the assistance of Chief Marketing Officer Mike Solana, Thiel has used these qualities to manifest considerable soft power. Founders Fund’s cultural weapons include “Zero to One,” Silicon Valley’s philosophical manifesto, and the Thiel Fellowship. Recent initiatives like Hereticon conferences and Pirate Wires media have extended its sway.

Throughout the 2010s and into the 2020s, Founders Fund built true cultural influence. But could it use that power to build the future it preached?

Part IV: The Kingdom

Cracks in the meritocracy

There are other, louder indicators, but a telltale sign that a venture capital firm is out of ideas and running to fat is when it launches an incubation strategy. Frustrated with high prices or insufficiently interesting opportunities, managers follow a logical path: Instead of waiting for the next billion-dollar business to walk through our door, why don’t we just build one? How hard could it be?

That so few great companies have arisen from venture incubations answers the question. Outside of Snowflake, there’s a paucity of truly colossal companies that have grown out of this model within the past couple of decades. (Though programs like Y Combinator are occasionally referred to as “incubators,” they do not operate the same way, giving founders with existing early-stage businesses capital and guidance, rather than conceiving of an idea in-house and hiring management to build it.)

Founders Fund is an improbable exception. Its religious belief in the importance of outlier founders could have conflicted with the plug-and-play approach many incubations take; the next Mark Zuckerberg will not join a pre-made company as an outside CEO.

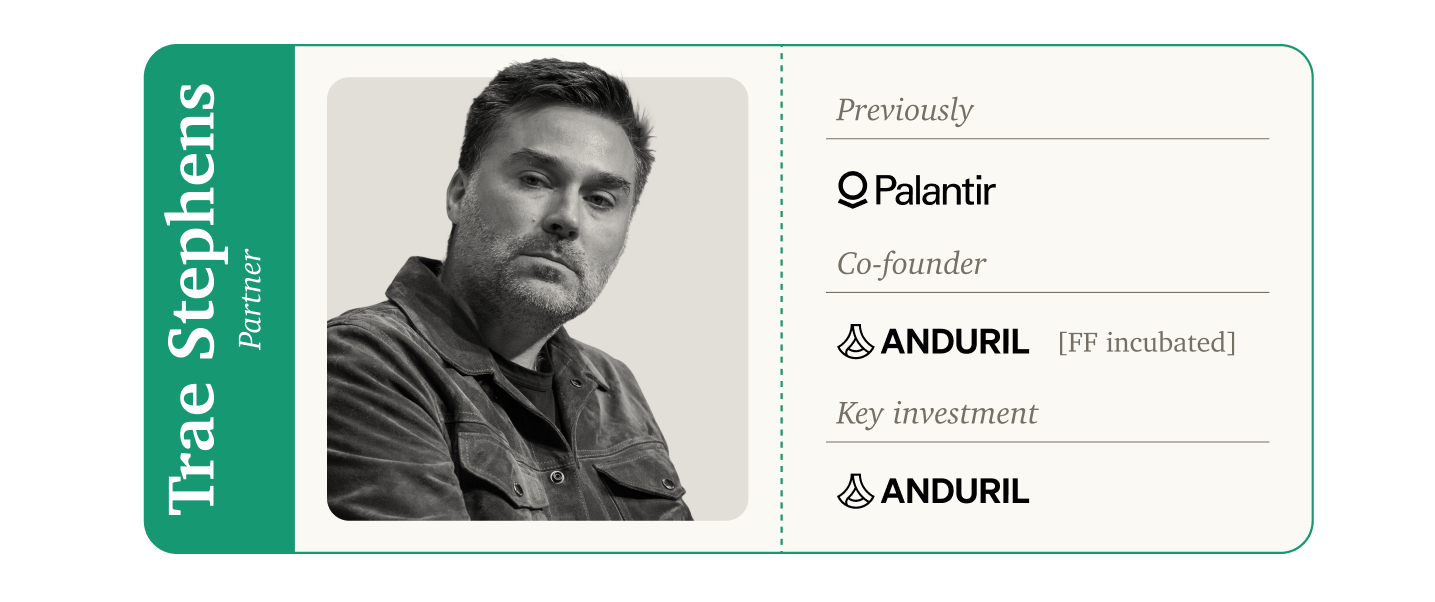

It has no dedicated program guiding its approach. And yet in Anduril, it functionally incubated one of the most consequential companies of the past decade. In Varda and General Matter, it appears to have two other highly promising businesses coming down the pike. (It also deserves partial credit for Palantir, given Thiel’s involvement as co-founder and first backer, but as we’ve noted, its origins predated the firm.) The introduction of this strategy owes much to the arrival of Trae Stephens.

There is something of the Paul Bunyan in Stephens’s story, renovated for the modern era. He was raised in rural Ohio, thirty miles northeast of Cincinnati, in a log cabin his father had built entirely with his own hands. His mother, a “salt-of-the-earth Midwesterner,” worked a series of jobs to help support the family, taking positions as an executive assistant, librarian, and math teacher during his youth. They lived paycheck to paycheck much of the time.

Though Stephens’s father had no college education, he’d built a career for himself as a roller-coaster engineer, a less unusual job than you might think in that part of the country. “You know there’s those T-shirts that say, ‘Virginia is for lovers,’” Stephens said, referring to the state’s popular slogan. “Well, the Ohio shirt is ‘Ohio is for coasters.’”

His father’s job brought enviable perks for the young Stephens. “We grew up going to amusement parks constantly,” he recalled. “We were the weird family that didn’t have to pay for anything. My dad would take me to work with him and I’d ride all the rides before the park opened.”

Beyond reveling in the screaming drops and loop-de-loops of Kings Island and Cedar Point, Stephens developed an early passion for reading. “From as early as I can remember, the last hour of our night every night was my whole family sitting in the living room reading in silence,” he said. “As a parent now, I ask myself, ‘How did my mom and dad pull that off?’” That developed into a love of writing, which Stephens leveraged to write puckish columns as editor of his high school paper. (Is that Peter Thiel’s leitmotif playing?)

“I got into a bunch of trouble trolling people,” Stephens said, recalling one particularly controversial edition of his “Politicks” column on how poorly mental health drugs performed compared with placebos. “I was stirring the pot probably too much for a 17-year-old in rural Ohio. People thought I was saying that mental health isn’t real. My principal had to talk to me about staying in the box after that.”

Stephens envisioned a future as an intrepid investigative journalist working for a leading international publication, and applied to the universities best-known for grooming such talent.

On September 11, 2001, his plans changed. “It happened on a dime,” he said. “I was sitting in my principal’s office watching the footage and I just blurted out, ‘I want to do something in service to the country. I don’t think I want to do journalism anymore.’” Instead of Columbia or Northwestern, Stephens now dreamt of going to Georgetown and building a career in the public sector.

There was only one problem — he was rejected. His pain was compounded when on the same day that he received the “skinny letter” from Georgetown, his high school girlfriend broke up with him. Rather than crush Stephens’s spirit, the double rejection seemed to ignite something in him. And so when his mother suggested he fly to Washington, D.C., and try to convince the university’s admissions officers to let him in, Stephens felt motivated enough to give it a shot.

That led to him sitting on the steps outside of the admissions office, clutching a stack of recommendation letters he’d collected from high school teachers. “I literally just sat there and said, ‘I’m not leaving until I speak to the Dean of Admissions.’” Stephens admits that it would make for a more dramatic story had he been left idling for hours, ideally overnight.

In reality, it took about thirty minutes for the dean to bring him in and ask, one imagines with the exhaustion of someone who has just told tens of thousands of dreaming students “no,” “What do you want?”

Stephens made his pitch, stacking his envelopes on the table between them. “I said, ‘I don’t know what else to do. I really want to go to school here. I have literally perfect standardized test scores, I’ve never gotten a B in my entire life, I’m valedictorian of my high school class and a three-sport varsity athlete. I don’t understand.”

Stephens recalled the dean’s sigh and the precise words he uttered next: “You have to understand, there are cracks in the meritocracy.”

Stephens left with his name at the top of Georgetown’s waitlist. He got in. That fall, he started school in the nation’s capital, going on to major in Middle Eastern Studies.

In the years that followed, he leveraged the school’s network to begin his career in the public sector and intelligence communities, working for Afghanistan’s D.C. embassy while at school. “I had a very close personal relationship with multiple members of the Karzai family,” Stephens said, referring to former president Hamid Karzai. “It was a crazy experience to have as basically a teenager. The most important international relationship of the early 2000s was with the transitional government of Afghanistan. To accompany the president of Afghanistan to meetings at the White House and read through briefing books with him was wild.”

After graduation, Stephens joined the staff of Ohio Senator Rob Portman, before moving into the intelligence community, where he sat “in the basement of a concrete building doing natural language processing” for two and a half years. His knowledge of Arabic and self-taught coding skills made him an asset to the agency in question’s computational linguistics efforts.

It was in that seat that Stephens saw an early demo of Palantir. Immediately, he recognized its value. “I went back to my team and said, ‘This would save me so much time, probably a day a week of work.’”

Despite his urging, Stephens was unable to get his higher-ups to consider adopting the software. Frustrated, he reached out to the Palantir executive who had given the demo, future CTO Shyam Sankar. “I said, ‘I hope you’re not wasting your time; this isn’t going anywhere. I’ve been trying to fight the battle internally.”

Sankar was unfazed. “Shyam just responded, ‘LOL’” Stephens said. The Palantir executive then followed it with a question: “I’m not trying to push my luck, but what are you up to?”

Not long after, Stephens found himself standing in Palantir’s Palo Alto workspace, dressed in a suit, tie, and cufflinks. Meanwhile, Sankar had just spent the night sleeping on a cardboard box in his office. “He still makes fun of me for it,” Stephens said. A whirlwind few hours followed, with Stephens meeting Palantir CEO Alex Karp and future Anduril co-founder Matt Grimm. When Stephens received a job offer at the end of the daylong gauntlet, he accepted on the spot.

Stephens spent nearly six years at Palantir, participating in its maturation from fledgling startup to a mature growth-stage business serving Western-allied governments around the world. It was during that spell that he was acquainted with the company’s first investor, Peter Thiel, though Karp delayed introducing the pair for as long as he could muster.

“About two years into my time at Palantir, I had this conversation with Dr. Karp, I forget what about,” Stephens said. “I asked him a question about Peter and he said, ‘Trae, I’m never going to let you meet Peter.’ I was like, ‘Oh. That’s weird. Why?’ And he said, ‘If you meet Peter, Peter will like you too much and he’ll try to poach you, and that will be that.’”

For two years, Karp managed to keep Stephens out of Thiel’s clutches, but in 2012 the pair met. A friendship quickly formed. “We just really hit it off, and every time he was on the East Coast, we’d get together and have breakfast,” Stephens recalled. Their shared Christian faith was a particular point of connection, as were their voracious reading habits. “Peter loves talking about deep theology stuff. He would assign books for me to read before the next time we got together. We really connected over that stuff,” Stephens said.

As Karp had prophesied, a job offer followed. In March 2013, Thiel told Stephens that his venture firm was closing in on its first billion-dollar fund and he wanted him to join. “He was my boss, the co-founder of the company I worked for, so it was not at all clear if it was an order or an offer,” Stephens said. Nevertheless, he agreed to meet with Founders Fund’s team, connecting with Lauren Gross, Brian Singerman, Mike Solana, and Geoff Lewis while they visited New York.

“It was a disaster,” Stephens said of that first meeting. “Lauren was like, ‘Why am I talking to you?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know, Peter told me to talk to you.’ Then she asked, ‘Why are you interested in venture capital?’ and I was like, ‘To be honest, I’m not really.’” It made for an awkward encounter.

Perhaps because of that, it took nine months for Stephens’s offer to arrive. With typical theatricality, Thiel officially sent it over on Thanksgiving Day, 2013. Stephens still knew next to nothing about venture capital, but he’d warmed up to the idea, especially after the birth of his first child. An investor’s schedule seemed vastly favorable to the unrelenting hours he’d been putting in at Palantir. He accepted, feeling it was “as good a time as any to transition.” Little did he know that within a matter of years, he’d look back on the hours Palantir required as the equivalent of a “lifestyle job.”

But first, there were three and a half years of learning the venture craft. At Brian Singerman’s advice, Stephens committed to take 500 pitches in his first year, ending his first twelve months with 504 under his belt. “It was a crazy pace,” he said. “There’s no reason to meet with that many companies unless you’re in your first year of venture capital. But eventually, you start to be able to make a decision in five minutes. You can sit in a meeting and say, ‘This is a definite no.’ And occasionally, very occasionally, you meet someone and you start feeling that flutter of ‘There’s something special.’” Stephens experienced that twice his first year, falling in love with Flexport and Qadium (renamed Expanse and now Cortex Xpanse), a security startup. The latter sold to Palo Alto Networks for $800 million in 2020.

While Stephens immersed himself in tech’s vast salmagundi of sectors, his mind inexorably returned to matters of national security: Why hadn’t anyone built a modern defense prime for the software era? If America was to remain a global superpower, Stephens knew its military needed continued innovation. He set his sights on finding a startup to back. He met with more than a hundred but came away from those conversations believing that none had the correct approach. And so, in 2017, he set out to build a company of his own — while retaining his role at Founders Fund.

The result was Anduril, co-founded by Stephens, Palmer Luckey, Brian Schimpf, Matt Grimm, and Joseph Chen. It is America’s most consequential and valuable defense startup since SpaceX, with a recent fundraise reportedly valuing the company at $30.5 billion.

As you might expect, Founders Fund was Anduril’s first backer and is its largest external shareholder. It has invested $1.4 billion in the company, the most the firm has ever invested in a single startup. The latest figures show that stake is currently valued at $5.3 billion.

Space, drugs, arms, and uranium

Varda looks like the firm’s next homegrown success. Founded in 2021 by partner Delian Asparouhov and SpaceX engineer Will Bruey, Varda is another example of Founders Fund’s creativity and ambition.

Born in post-Soviet Bulgaria, Asparouhov’s family had emigrated to the United States in the mid-1990s. As a child, he’d shown a remarkable proclivity for mathematics, benefiting from the tutelage of his statistician father. He competed regionally in the U.S. and spent one of his summers training alongside Bulgaria’s mathematics and informatics national teams.

In early high school, though, Asparouhov’s interests began to change. He found himself increasingly absorbed by robotics and space. Friends would later remind him that as early as 9th or 10th grade, he’d spoken about the commercial promise of space manufacturing.

Beyond it being undeniably cool, you might wonder why anything should be manufactured extraterrestrially. Space’s unique properties afford unusual advantages. Materials mix and interact differently in zero gravity, for example, and extreme temperatures can prove useful for certain processes. Because of the costs involved in bringing materials to space, low-orbit manufacturing has been considered an intriguing prospect for high-value pharmaceutical products and semiconductors. As the final frontier opens up, manufacturing items intended for space in space — satellites, for example — is also expected to become economically advantageous.

Asparouhov could not have fully considered the nuances of this as a high schooler, but he was sold on the need and promise. “I really wanted humanity to have a multiplanetary future,” he said, “but especially one with anti-communist ideas because of my upbringing in Bulgaria. I didn’t really believe that state governments would be the way that happened. Ultimately, it needed to be a private industry, and obviously private industry is fundamentally motivated by profits. That’s why I was obsessed with the idea of: How does one make profits in space?”

Asparouhov maintained that interest through two years at MIT, early entrepreneurial forays, and a budding venture career. Space tech was never his primary focus but a steady obsession that took him to wonkish aerospace conferences and consumed his nights and weekends. In the process, he gained a greater appreciation for the challenges of building commercially viable space companies. “I started meeting with a lot of founders operating in the space and learned how difficult it was to pull off these types of businesses,” Asparouhov said. That began to erode his enthusiasm. “I got somewhat disinterested in the idea for a time, given how complex it was.”

An event at the end of 2019 reignited his excitement: SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket launched and landed four times in a row. It was a breakthrough, showing that reusable rockets were viable. Suddenly, the heavens looked exponentially more open. Asparouhov reached out to friends in the industry to validate his reading. How reusable were these rockets? Could the Falcon 9 take off and land 40 times in a row, rather than just the four it had demonstrated? “The resounding feedback I got was, ‘There’s no reason we can’t get to 40.’”