No Rivals: The Prophet (Part I)

Founders Fund, led by Peter Thiel, has ascended to the pinnacle of Silicon Valley. Its fundamental genius is wanting differently.

“The Generalist offers the most in-depth, well-researched, and thought-provoking insights.” — Alya, a paying member

Friends,

In January of 2024, we asked you, our readers, which startup or venture fund you most wanted us to cover in a deep dive. The answer was unequivocal: Founders Fund.

Over the past 18 months, we’ve been working on that story. Today, at long last, we’re sharing the fruits of those efforts.

“No Rivals” is a four-part series spanning more than 35,000 words. It will run over the next four weeks. It’s the most comprehensive examination of Silicon Valley’s most controversial venture firm, its extraordinary performance, and its remarkable cultural influence. The series is the product of extensive research, interviews with more than a dozen key figures, and a detailed analysis of Founders Fund’s previously undisclosed returns.

It’s a story featuring globally visible characters—Thiel, Musk, Altman, Zuckerberg, Trump—and secretive power brokers who shun the spotlight. It’s a story of philosophy and technology, spite and vision, political maneuvering and spectacular windfalls.

Given the depth and exclusivity of this reporting, the full series is available only to subscribers of our premium newsletter, Generalist+. For $22 per month or $220 per year, you’ll get unprecedented access to Founders Fund’s performance data, detailed case studies of their biggest wins and losses, and insights into how they’ve shaped Silicon Valley and Washington. If you work in tech, venture capital, or traditional investing, this series alone should more than justify a year’s subscription.

Part I: The Prophet

Peter Thiel was nowhere to be seen.

On January 20, escaping a bitter winter storm, America’s most powerful gathered beneath the Capitol dome to celebrate Donald J. Trump’s inauguration as the 47th president.

The usual suspects were in attendance, mingling with a new guard: UFC impresario Dana White lurking a few feet behind Barack Obama, George W. Bush a simple football toss away from Joe Rogan, OpenAI’s Sam Altman conversing excitedly with influencer Logan Paul. Welcome to the New America; you don’t need a podcast to work here, but it helps.

If you have even a passing interest in technology and venture capital, it is difficult to review photos from the event and not think of Thiel. He does not appear once, and yet he is everywhere.

There is his former employee, now the Vice President of the United States. A few feet away is an old Stanford Review buddy, newly named Trump’s “AI and crypto czar.” Further along sits one of his first angel investments, the CEO and founder of a little company called Meta. Next to him is a friend turned nemesis turned partner — the founder of Tesla and SpaceX, ringleader of DOGE, and richest man in the world. Thiel’s favorite philosopher, René Girard, describes divinity as a kind of “transcendental absence.” Studying the figures swarming beneath a fresco of George Washington’s apotheosis, this is the quality of Thiel’s presence and non-presence.

It would be too much to say that Thiel designed such a moment. But throughout his career, the former chess prodigy has shown an uncanny gift for seeing twenty moves into the future and pushing key pieces into position: JD to b4, Sacks to f3, Zuck to a7, Elon to g2, Trump to e8. He does so across power centers, moving between New York finance, Silicon Valley tech, and Washington’s military industrial complex. He employs a puzzling blend of discretion and impropriety, disappearing for months on end only to pop up with a spiky bon mot, a head-scratching new investment, or a titillating vendetta. Many of these maneuvers look like blunders at first, only for time to reveal them to be indications of stunning foresight.

At the heart of Thiel’s power, influence, and wealth is Founders Fund. No organization has benefited more from his singular abilities, and those of the team he has assembled, than the venture firm. Since launching in 2005, Founders Fund has grown from a $50 million inaugural fund, with a novice investing team and little brand equity, into a Silicon Valley powerhouse, boasting billions under management and what looks like the best full-stack investing team in the industry. It has done so while cultivating a polarizing, piratical image — venture capital in the styling of the Oakland Raiders or the “Bad Boy” Pistons of the early 1990s, if Dennis Rodman adored Leo Strauss.

The numbers have justified Founders Fund’s swagger. Concentrated bets on SpaceX, bitcoin, Palantir, Anduril, Stripe, Facebook, and Airbnb have delivered a string of hit vintages even as fund sizes have grown. In its 2007, 2010, and 2011 vehicles, Founders Fund can lay claim to a trio of the asset class’s best-ever vintages, producing gross multiples of 26.5x, 15.2x, and 15x from $227 million, $250 million and $625 million, respectively.

The Generalist has spent over a year studying Thiel’s firm, its ascent to the pinnacle of Silicon Valley, remarkable influence, and impact it has had on the venture capital industry and the world beyond. It is a story populated by many of tech’s most vivid characters and marked by unpopular choices, sharp elbows, and, yes, contrarian thinking. More than anything, Founders Fund is a story about the power of wanting differently. In an asset class predisposed to posturing and mimesis (one of Thiel’s pet subjects), Founders Fund has succeeded by directing its desires uncommonly.

To build this picture of Founders Fund, The Generalist interviewed over a dozen sources, including leadership, longtime LPs, and some of the exceptional entrepreneurs the firm has backed. We have also reviewed fund material, including a detailed picture of Founders Fund’s performance. The result is the definitive case study of an outlier organization.

Pals

If you do not want to work for Peter Thiel, you must avoid meeting him.

The French diplomat Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, Napoleon’s foreign minister, was said to be so interesting, so charming, that it was almost dangerous to spend too much time in his company. Contemporaries described his smile as “paralyzing,” while the salonist Madame de Staël, no stranger to grandiloquence, gushed of Talleyrand, “If his conversation was for sale, I should ruin myself.”

Peter Thiel seems to have a similarly transfixing effect. In studying Founders Fund’s origins, evidence of this referent power appeared repeatedly: a chance encounter with Thiel bewitching the listener to move cities, forgo prestige, and alter career plans, to spend a little more time in the strange moonlight of his mind.

Listen to Thiel speak — on the stage at a conference or during a rare podcast appearance — and it’s plain his magnetism does not come from a diplomat’s oleaginous patter. Rather, it stems from a polymathic ability to dance across subjects, to frame a conversation as an invitation into a secret, to red-pill with the sophistication of a tweed-jacketed Trinity College professor. Who else can write a canonical book on startups by way of Lucretius, Fermat’s Last Theorem, and Ted Kaczynski that also argues for the virtuousness of monopolies and the wisdom of running one’s business like a cult? How many other minds contain this range of rigor and irreligion?

Before forming Founders Fund with Thiel in 2004, Ken Howery and Luke Nosek fell under his spell years earlier.

Ken Howery’s conversion experience arrived as an economics undergraduate at Stanford. In Zero to One, Thiel’s business philosophy book published in 2014, he describes Howery as the only one of PayPal’s founders to “fit the stereotype of a privileged American childhood,” the company’s “sole Eagle Scout.”

Born and raised in Texas, Howery moved to California in 1994 for college, where he began writing for The Stanford Review, a conservative student publication Thiel had co-founded seven years earlier. It was through the Review that Thiel and Howery first met, connecting at an alumni event in his early years at Stanford. They stayed in touch as Howery progressed through his education and rose to the position of managing editor in his senior year.

Ahead of the Texan’s graduation, Thiel presented an offer: Would Howery like to be the first employee at Thiel’s fledgling hedge fund? He suggested the pair discuss the opportunity over a meal at Sundance, a Palo Alto steakhouse. It did not take long for Howery to realize that this would not be a traditional recruiting dinner. What followed was a four-hour tour of Thiel’s mind, with the upstart investor in full mesmer mode.

“Everything we talked about, from politics to philosophy to entrepreneurship — I felt he had more interesting views on them than almost anyone I had met during my four years at Stanford,” Howery recalled. “I was super-impressed by the breadth and depth of his knowledge.”

In spite of that, Howery wasn’t ready to commit to Thiel’s offer on the spot. He said he’d have to think it over. But when he returned to campus that evening, Howery recalled telling his girlfriend, “I think I might work with this guy for the rest of my career.”

There was just one impediment: Howery had intended to move to New York for a well-paid banking job at ING Barings. In the weeks that followed, the Stanford senior conducted an informal survey. He asked his family and close friends which of the two jobs he should take: the lucrative, prestigious Barings position or the hazy post with a new acquaintance of unknown abilities and just $4 million under management? “One hundred percent of them told me to take the bank job,” Howery said. “I thought over it for a few weeks and decided to ignore their advice and do the non-obvious thing.”

Before graduation, Howery attended a talk his new boss was giving on Stanford’s campus. A pale young man with a crop of brown curly hair sat next to Howery and, before the lecture began, leaned over and asked him if he was Peter Thiel.

No, Howery told him. But I’m working for him.

The young man introduced himself as Luke Nosek, passing Howery a business card that said, simply, “Entrepreneur.” I build companies, Nosek explained.

“I was just instantly fascinated,” Howery said.

As it turned out, Nosek was building a company that Thiel had already backed: Smart Calendar, one of a flush of digital timetables that emerged around the same time.

The interaction raises a puzzling question: How had Nosek forgotten the face of one of his backers, someone he’d shared several breakfasts with? Perhaps it had been a long time since their last meeting. Or perhaps an eccentric, driven founder put little stock in the facial composition of his money man. Or just maybe, Thiel was, for a brief moment, forgettable.

Though Nosek didn’t recall his first encounter with Thiel in high fidelity, Thiel certainly seemed to. In Zero to One, he recounted how in that initial conversation, Nosek explained that he’d arranged to be cryonically preserved upon death, in hopes of being resurrected in the future. In Nosek, Thiel found something he would come to use as a kind of talent archetype: a startlingly brilliant and undeniably odd individual, willing to reason to conclusions that others were too timid to consider. That mixture of cerebral horsepower, intellectual liberty, and disregard for social mollification spoke to something in Thiel, perhaps because it reflected so much of his own demeanor. Thiel soon followed Nosek’s lead, giving control of his remains to cryogenic provider Alcor.

As of that Stanford talk in mid-1998, all three of Founders Fund’s founding fathers had officially met. Though it would take another seven years for the trio to launch their venture fund, a deeper collaboration began almost instantly.

Spite Store

“Hi, I’m Larry David and I want to tell you about a new store I’m opening called Latte Larry’s.”

So begins episode 9, season 10 of Curb Your Enthusiasm, the meta comedy of manners from Seinfeld’s legendary creator. “Why am I getting into the coffee game?” David continues. “Because I went to the coffee shop next door and the guy was such a jerk that I felt like I had to do something. Now, you know what? I’ve got me a little Spite Store.”

With that, David added another phrase to the cultural lexicon, alongside Seinfeld favorites “close talkers,” “master of my domain,” and “sponge-worthy.”

Spite Store, noun. A commercial enterprise used to exact revenge on a rival by competing for their customers.

At least on one level, Founders Fund was Peter Thiel’s spite store. While the snippy “Mocha Joe” motivates Larry David, Thiel’s endeavor can be viewed as a response to Sequoia Capital’s Michael Moritz. An Oxford-educated journalist by training, Moritz is one of venture capital’s true legends, responsible for early investments in Yahoo, Google, Zappos, LinkedIn, and Stripe. An investing power slugger with a literary bearing, Moritz appears at regular intervals throughout the early part of Thiel’s story, foiling his plans and slighting his allies.

It all began at PayPal.

The same summer that Thiel recruited Howery, he met Max Levchin, a talented Ukrainian-American entrepreneur. Like Nosek, Levchin had graduated from the University of Illinois, where he’d built a profitable encryption product for PalmPilot owners. Over smoothies, Levchin convinced Thiel of its promise. “That’s a good idea,” Thiel said. “You should do that. And I’d like to invest.”

Though he could not have known it, Thiel was not only making an exceptional investment decision — his $240,000 check would ultimately deliver a $60 million windfall — but entering into the dotcom era’s most vivid opera, which alternated between tragedy, farce, and, ultimately, triumph. (The Founders offers a full accounting.)

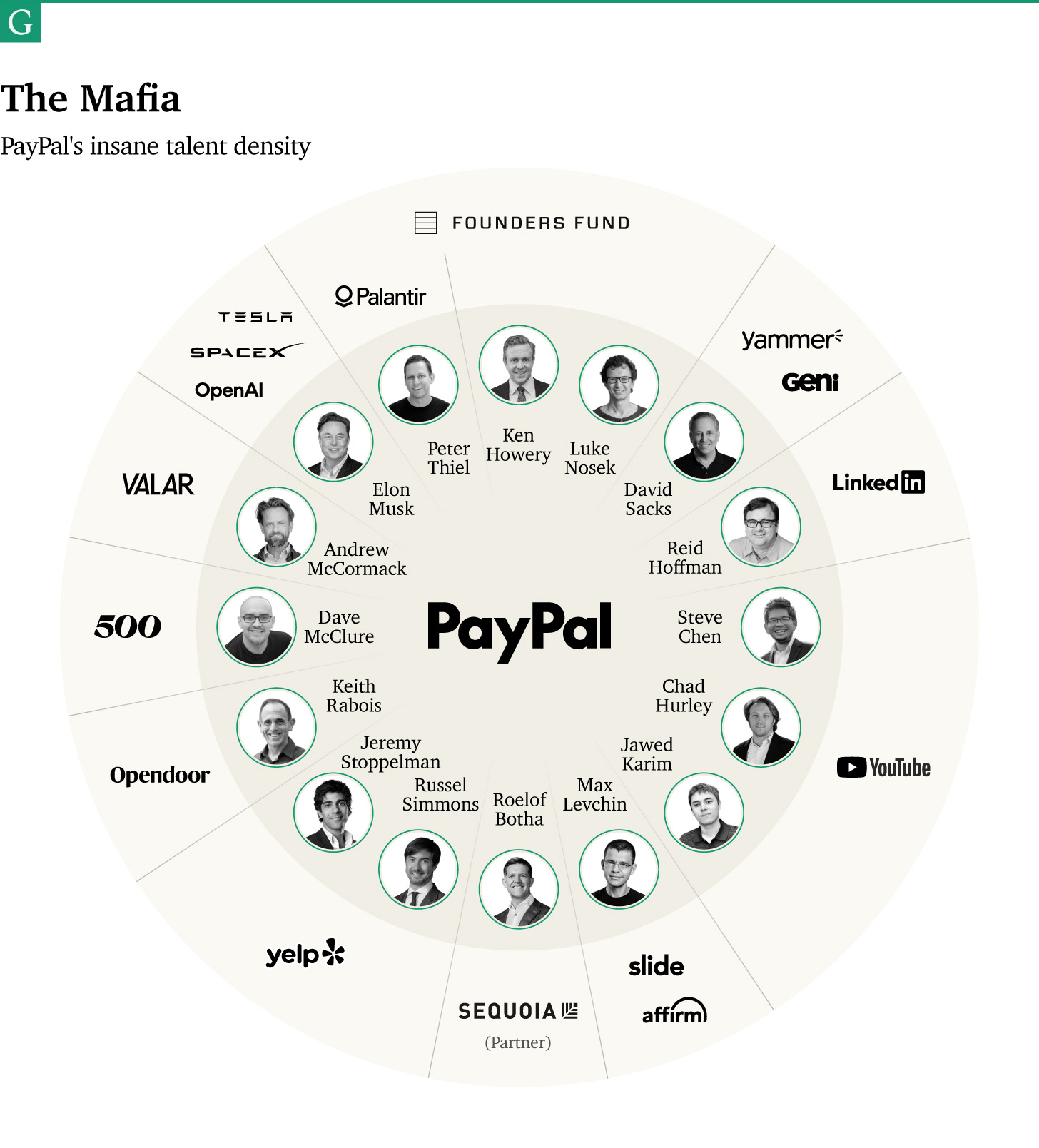

Levchin quickly recruited Nosek, whose calendaring company had died. Shortly after, Thiel and Howery joined as full-time employees, with Thiel taking on the CEO mantle. Reid Hoffman, Keith Rabois, David Sacks, and many others would follow to form one of the most talent-rich startups in Silicon Valley history.

It did not take long for the company — originally named Fieldlink, before rebranding as Confinity — to collide with rival firm X.com, run by a brash South African entrepreneur named Elon Musk. Rather than burn through their capital in an extended war, Confinity and X.com agreed to join forces. They named the combined company after Confinity’s most popular feature, which connected email addresses to payments: PayPal.

The merger not only meant annealing two opinionated management teams but welcoming the other party’s investors. Moritz, who had invested in Musk’s X.com, suddenly had to wrangle with a new cadre of awkward geniuses.

The first indication that Thiel and Moritz were a marriage of strained convenience arrived on the back of the merger. The same day the companies announced their partnership to the press, March 30, 2000, they shared the news of an $100 million Series C.

Thiel had been critical in pushing the round to a definitive conclusion, concerned by what he saw as a worsening macroeconomic backdrop. His concerns proved prescient. In a matter of days, the dotcom bubble had begun to burst, sending many of the era’s buzziest names toward painful deaths. By pushing to get the deal across the line, Thiel had saved PayPal from a similar fate. “I give the credit to Peter,” one employee said. “He made the macro call and said, ‘We have to close on this … because the end is near.’”

It wasn’t enough that his shrewd macro reading had saved the company, though. Thiel, a hedge fund investor by disposition, saw an opportunity to turn a profit. At a meeting with PayPal’s investors in the middle of 2000, Thiel made his modest proposal: if the markets were poised to drop further, as he believed they were, why not short them? All PayPal needed to do was transfer its new $100 million war chest to Thiel Capital International and he could take care of the rest.

Moritz was apoplectic, and reasonably so. Thiel was asking for permission to gamble with company money during an economic bloodbath. “Peter, this is really simple: if the board approves that idea, I’m resigning,” another board member remembered the Sequoia investor warning. For his part, Thiel couldn’t understand such a hidebound reaction. The fundamental divide was between Moritz’s desire to do right and Thiel’s to be right. It was not easy to find common ground between those two epistemological poles.

In the end, both won and both lost. Moritz succeeded in thwarting Thiel’s plan, but Thiel was right: the market tanked. If they’d had the right positions, PayPal and its backers could have made a killing. “We would have made more money [investing] than anything we did at PayPal,” one backer said.

If that boardroom debacle fed a fermenting distrust between the two men, a clash just a few months later ensured that it did not heal. In September 2000, PayPal’s employees — led by Levchin, Thiel, and Scott Banister — staged a coup against current CEO Elon Musk. PayPal did a good line in coups in those days, having launched a putsch against short-lived outside CEO Bill Harris.

That had been a relatively bloodless affair, but, true to form, Musk did not go quietly. To get him out the door, Thiel’s insurgent force had to convince Moritz to ratify their plan to give Thiel control of the company. The Sequoia investor did so, on one condition: Thiel could become CEO, but only on an interim basis.

As it happened, Thiel had little interest in being PayPal’s long-term CEO. His skills lay in the cerebral rather than the logistical. But Moritz’s edict forced him into the humiliating position of hiring his replacement. Only after the leading outside candidate told Moritz that even he would recommend appointing Thiel full-time did the Sequoia investor abandon his initial plan. The push-and-pull of being asked to step aside only to be anointed full-time CEO aggravated Thiel, a man with a talent for holding a grudge.

Despite PayPal’s formidable dysfunctions, it survived and ultimately succeeded. Thiel had Moritz to thank for the scale of the outcome. In 2001, eBay offered to acquire PayPal for $300 million. Thiel considered it a good offer and advocated for a sale, while Moritz pushed for PayPal to hold out. “He was the hedge fund guy,” Moritz later said of Thiel, “Wanted to take all his money out. I mean, goodness gracious.” Thankfully for all involved, Moritz convinced Levchin of his side of the argument, and PayPal stayed independent. Not long after, eBay returned with a better offer: $1.5 billion, five times the figure at which Thiel had advocated exiting.

It made Thiel and the rest of the company’s “Mafia” very wealthy men, while Moritz added another hit to his growing tally. Had they been different people, perhaps time might have sanded down the enmity between Thiel and Moritz, grading into begrudging friendship. Instead, it was the first act in an ongoing battle.

Clarium calls

As the thwarted $100 million macro bet suggested, Thiel had never lost the investing bug. Despite PayPal’s demands, he and Howery continued to manage Thiel Capital International. “We worked a lot of nights and weekends, making sure it was still going,” Howery said.

Befitting Thiel’s broad interests, they cobbled together a salmagundi of a portfolio, mixing equities, debt, foreign exchange, and early-stage startups. “We did about two or three deals per year,” Howery recalled, highlighting IronPort Systems as an especially shrewd bet during that period. Founded in 2002, the email security provider later sold to Cisco in 2007 for $830 million.

Thiel’s $60 million windfall from PayPal’s acquisition poured gasoline on his ambition and investing. Even as he scaled assets under management, he seemingly couldn’t help himself from moving in multiple directions at the same time, chasing macro investing greatness, formalizing his venture practice, and founding another company.

Clarium Capital was at the heart of these efforts. The same year the PayPal acquisition closed, Thiel turned his attention to launching the macro hedge fund. “We are trying to pursue a systemic view of the world like that which Soros and others said they pursued,” Thiel explained in a 2007 Bloomberg profile.

It seemed a perfect fit. Thiel naturally thought in grand, civilizational trends and was congenitally disposed to disagree with whatever the moment’s prevailing wisdom happened to be. It did not take long for him to demonstrate how that lens, when applied to market problems, could produce impressive returns. In just three years, Clarium climbed from $10 million in assets under management to $1.1 billion. In 2003, Clarium logged a 65.6% gain betting on a weakened dollar; after a lackluster 2004, it sprang back to life the next year with a 57.1% return.

Around the same time that Thiel set to work building Clarium, he and Howery explored the idea of turning their ad hoc angel investing into a dedicated venture fund. It didn’t hurt that the numbers showed they had a knack for it. “At a certain point we looked at our track record and the IRRs were in the high double digits, in the 60% to 70% range,” Howery said. “We were like, ‘Wow, this is on a very part-time basis, without even focusing on it. What if we formalized this and created a fund around it?’”

It took a couple of years for those discussions to become concrete, but by 2004, Howery got to work raising a $50 million fund, initially called Clarium Ventures. As before, he and Thiel looped in Luke Nosek, who joined on a part-time basis.

Compared with the billion-plus the hedge fund was managing, $50 million seemed like a drop in the bucket. But even with the trio’s PayPal bona fides, it proved a challenging raise. “It was actually super-hard — much harder than I would have expected,” Howery said. “Nowadays, everyone has a VC fund, but back then, that wasn’t the case. It was a very unusual thing to do.”

Institutional LPs showed little interest in backing such a small fund. Howery initially hoped to convince Stanford University’s endowment to anchor, for example, but they stepped away after learning of the fund’s size. That left individual LPs. Even though many of their former colleagues had benefited from the acquisition as well, the trio were able to drum up only $12 million in external capital. Eager to get to work, Thiel decided to make up the shortfall himself, investing $38 million (76%) into Fund 1.

“The rough split was that Peter put up most of the money, and I was doing most of the work,” Howery said of those early days. Given Thiel’s other commitments, that division of responsibility was not so much a choice as a necessity.