No Rivals: The Disciples (Part II)

Peter Thiel is not a manager. But his singular eye for talent allowed him to assemble an unorthodox team that went on one of venture’s hottest streaks.

"The best long-form essays on VC & Private Companies. " — MS, a paying member

Friends,

A prophet without disciples is a madman.

Founders Fund would not have achieved a fraction of its success had Peter Thiel not succeeded in winning others to his cause.

None have been more important than two largely unheralded figures: Napoleon Ta and Lauren Gross. Ta is the investor behind Founders Fund’s best-performing growth investments. A former poker player, Ta prefers to keep such a low profile that he has repeatedly asked his team not to submit his returns to Forbes’ Midas List.

Meanwhile, Gross is Founders Fund’s most important operator. As COO and head of IR, Gross scaled the firm’s AUM into the billions of dollars, staffed its world-class team, and executed Thiel’s vision.

In Part 2 of “No Rivals,” our series on Founders Fund, we chronicle Thiel’s major disciples and their impact on the firm. In the process, we tell the stories of its investments in Spotify, Airbnb, DeepMind, Stemcentrx, Stripe, and several others.

Part 1 quickly became The Generalist’s most popular piece ever. If you missed it, you can catch up by reading it here:

Given the depth and exclusivity of our reporting, the full series is available only to subscribers of our premium newsletter, Generalist+. For $22 per month or $220 per year, you’ll get unprecedented access to Founders Fund’s performance data, detailed case studies of their biggest wins and losses, and insights into how they’ve shaped Silicon Valley and Washington. If you work in tech, venture capital, or traditional investing, this series alone should more than justify a year’s subscription.

Previously on No Rivals…

Peter Thiel, Ken Howery, and Luke Nosek launched Founders Fund in 2005 with a radical promise: to never remove entrepreneurs from their own companies. This was a direct challenge to the traditional activist VC model in general, and to Sequoia’s Mike Moritz, in particular.

The firm's early performance was extraordinary. Thiel's $500,000 Facebook investment delivered $1 billion in personal returns and a windfall for Founders Fund. Palantir generated an 18.5x multiple and $3.1 billion in distributions.

Guided by philosopher René Girard's theories on mimetic desire, Thiel deliberately avoided the social media gold rush after Facebook. Instead, Founders Fund pivoted to hard tech, a call that led them to their greatest ever investment: SpaceX. Today, that position is valued at $18.2 billion.

By 2008, Founders Fund had built a promising early reputation, but was still a bit-part player in Silicon Valley. To turn the firm into a force, Thiel needed to scale capital and build a team…

Part II: The Disciples

Thiel Cubs

Ever since PayPal’s acquisition, Peter Thiel had established his reputation as a hedge fund manager with an array of intriguing side projects: Frisson, a swanky San Francisco eatery; American Thunder, a short-lived magazine devoted to NASCAR racing; and, of course, his venture fund. Founders Fund was undoubtedly the most important of these less important things, but there was no question that Clarium Capital represented the barycenter around which the others orbited.

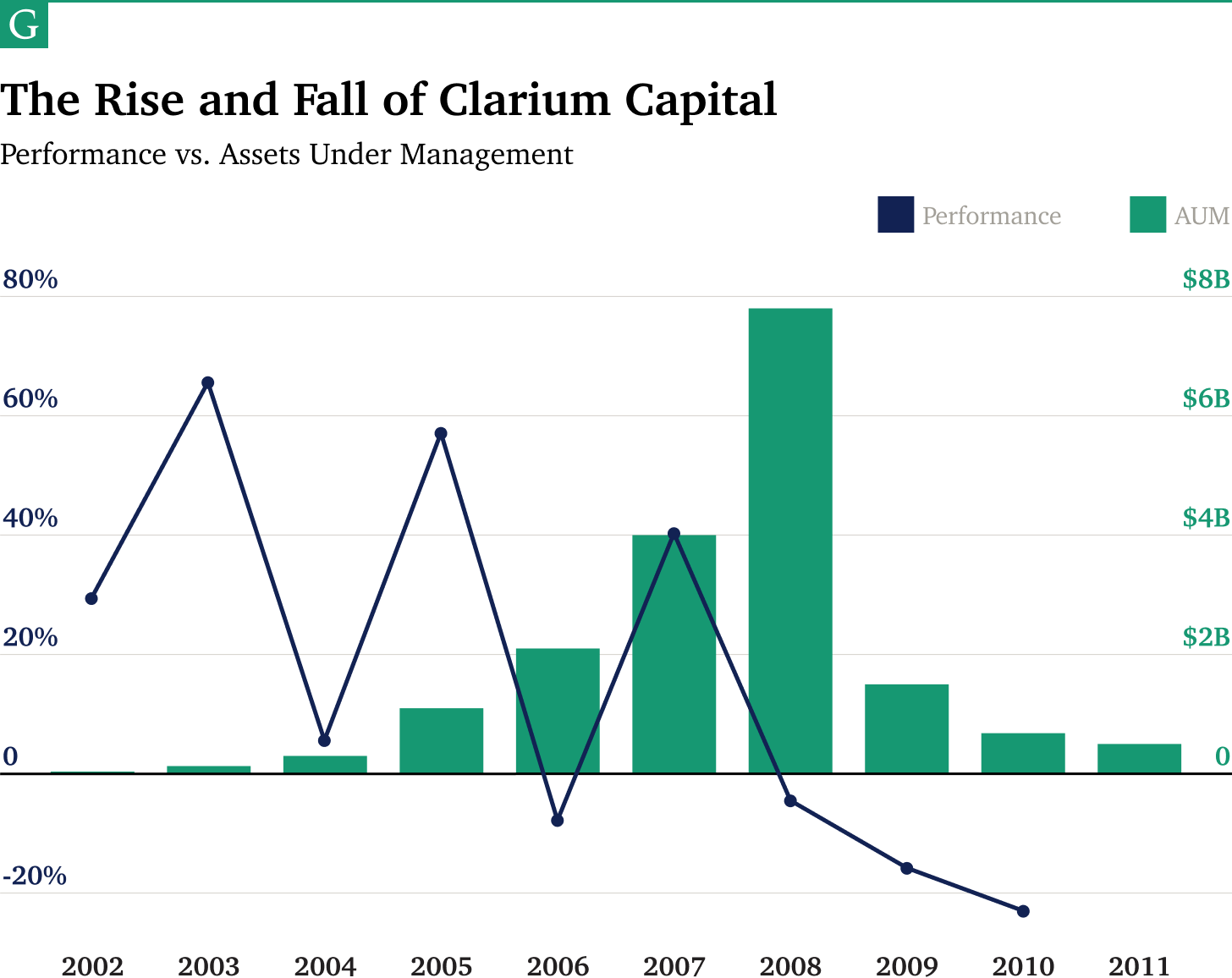

That began to change in 2008. The year started brightly, with Clarium coming off the back of a barnstorming 2007, up 40%, and sitting on over $7 billion in assets under management. Considering Thiel had founded the firm just six years earlier with $10 million, that rise was a testament to Clarium’s strong performance and Thiel’s growing reputation as a macro interpreter.

For several years, he had identified three thematic waves he intended to ride:

Rising 30-year U.S. Treasuries

The dollar outperforming the euro

Surging oil prices

During the first half of 2008, the world looked to be tilting even further in Thiel’s direction. While his peers in the hedge fund industry endured the “worst year on record,” Thiel racked up 59% in gains, driven by soaring oil prices.

They didn’t last. U.S. stocks crumbled to near-historic lows, and oil prices fell with them, erasing Clarium’s gains to leave it down 4.5% on the year. It never regained its footing, falling 25% in 2009 and a further 23% in 2010.

Investors fled, shrinking assets under management to approximately $500 million by 2011, down over 90% from its high. By then, most of it was Thiel’s own capital. The few LPs who stayed experienced a cumulative 65% drop between 2008 and 2011. By the end of that run, Clarium was effectively defunct. It would later get rolled into Thiel Capital, becoming a de facto family office.

Clarium’s demise was made more bitter by the fact that Thiel’s macro reading was largely sound. What scuppered it was not that Thiel had misconstrued the world’s shifting forces but that he, and the team, had been unable to translate those views into suitable trades. When the market turned in Clarium’s favor, it didn’t benefit as much as it should have; when the market turned against it, weak risk controls saw it incur mortal losses. In the end, Clarium posted annualized returns of 12% over the entirety of its history, but that didn’t help much when its worst years coincided with its fullest coffers.

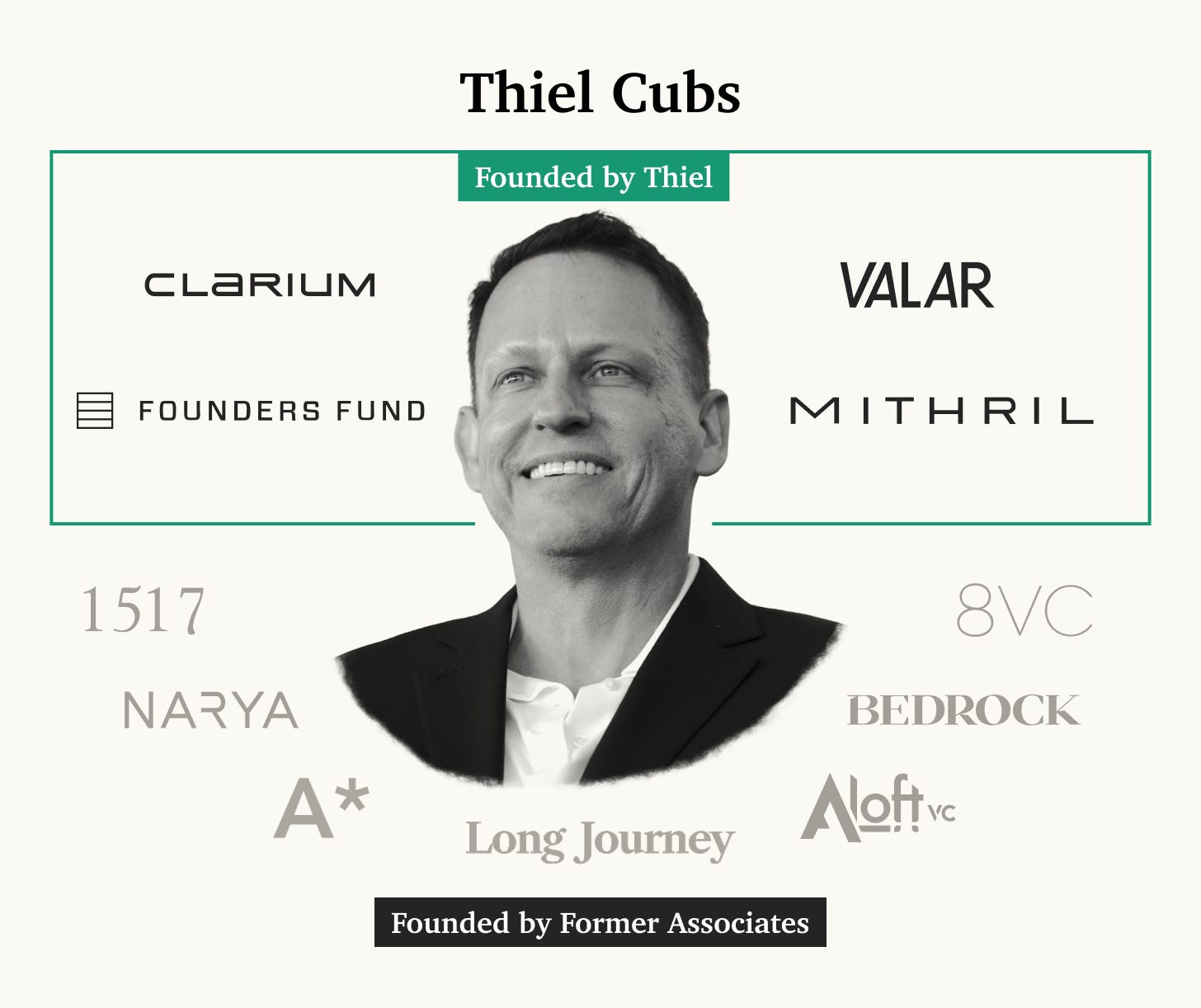

If there was a silver lining to Clarium’s collapse, it came on the talent side. Suddenly, a swath of anomalous Thiel-ites were free to take on new missions, bringing their leader’s eccentric view of the world into new organizations and domains. Many did so with Thiel’s backing, or at his direct behest.

Some stayed to manage Clarium’s remnants as it morphed into Thiel’s family office. Others were pushed to Founders Fund or Palantir, or left to launch funds of their own.

Unlike Julian Robertson’s “Tiger Cubs,” Thiel often co-founded these organizations — making him more partner than backer to his set of “Thiel Cubs.” Of these, Valar and Mithril hold the starring roles.

In 2010, Clarium alums James Fitzgerald and Andrew McCormack founded Valar Ventures with Thiel. It began with a simple, complementary premise: while Founders Fund focused on backing Silicon Valley’s elite entrepreneurs, Valar would search for outliers beyond California.

New Zealand was a particular focus in Valar’s early days. In 2011, Thiel became a Kiwi citizen, calling New Zealand a utopia and suggesting it could become a promising geography for tech innovation. Perhaps as a reflection of that belief, and to continue currying favor, Valar invested in companies from the country, initially through a series of special-purpose vehicles totaling $100 million.

Its first Kiwi investment was its best: Valar accumulated shares in accounting business Xero at just shy of $1.50 a share in 2010. By 2017, the $4 million invested was worth approximately $54 million.

As Thiel’s interest in New Zealand waned, and with opportunities abounding elsewhere, Valar’s focus shifted as the years passed. It progressively widened its aperture to include Europe and emerging markets. In 2013, it led a $6 million Series A in TransferWise (now Wise), which hit an $11 billion valuation at the time of its direct listing. Valar would also snag positions in neobanks Nubank and N26.

In recent years, it has evolved once again. Because of Thiel’s PayPal credentials, Valar has always shown particular aptitude in fintech. Today it leans on this aspect of its identity, rather than narrowing in on particular geographies. It raised a $300 million vehicle in 2024.

Mithril Capital arrived just two years after Valar. In 2012, Thiel and former Clarium managing director Ajay Royan launched a $402 million growth equity shop. They added another Clarium M.D., Jim O’Neill, to round out the initial team. By then, O’Neill had already done an extensive tour through several Thiel entities, moving from Clarium to the Thiel Foundation before launching the Thiel Fellowship, a program that gave $100,000 to talented college dropouts (more on that later).

Like Valar, Mithril’s initial positioning was complementary to Founders Fund. While Founders Fund focused on high-risk early-stage investments, Mithril was designed to back more mature businesses, such as surgical robot Auris and fundraising platform Classy. Auris looks like Mithril’s best investment thanks to a multi-billion-dollar acquisition from Johnson & Johnson.

Despite such results, Mithril’s history has not been a happy one. Though Royan announced his desire to build the “capstone” of Thiel’s empire, serious allegations about his management began to circle in 2019. That year, former counsel Crystal McKellar alleged that Royan had misled investors, artificially pumping its numbers to reap financial rewards. McKellar also alleged that she had been unjustly fired for reporting these issues. Jim O’Neill repeated similar claims in a lawsuit filed a few years later, alleging wrongful termination and “toxic” management from Royan. Ultimately, the FBI led a probe into Mithril, and prominent LPs like Cambridge Associates reportedly conducted internal investigations of their own.

No public charges have been brought against Mithril or Royan, but the firm nevertheless appears to be managing out its final days. It last raised a fund in 2017 and, as of 2023, was reported to have just $100 million left to deploy.

Despite its ostensible issues, Mithril did succeed in attracting strong talent, including future Anduril co-founder Matt Grimm and future Vice President JD Vance. Like so many before him, Vance had been bewitched by Thiel after attending his speech at Yale Law School:

I attended a talk at our law school with Peter Thiel…

He spoke first in personal terms: arguing that we were increasingly tracked into cutthroat professional competitions. We would compete for appellate clerkships, and then Supreme Court clerkships. We would compete for jobs at elite law firms, and then for partnerships at those same places. At each juncture, he said, our jobs would offer longer work hours, social alienation from our peers, and work whose prestige would fail to make up for its meaninglessness. He also argued that his own world of Silicon Valley spent too little time on the technological breakthroughs that made life better — those in biology, energy, and transportation — and too much on things like software and mobile phones. Everyone could now tweet at each other, or post photos on Facebook, but it took longer to travel to Europe, we had no cure for cognitive decline and dementia, and our energy use increasingly dirtied the planet. He saw these two trends — elite professionals trapped in hyper-competitive jobs, and the technological stagnation of society — as connected. If technological innovation were actually driving real prosperity, our elites wouldn’t feel increasingly competitive with one another over a dwindling number of prestigious outcomes.

The Hillbilly Elegy author would describe the encounter as the “most significant moment” of his time in New Haven. After leaving Mithril, Vance would join Steve Case’s Revolution, before founding a firm of his own, Narya.

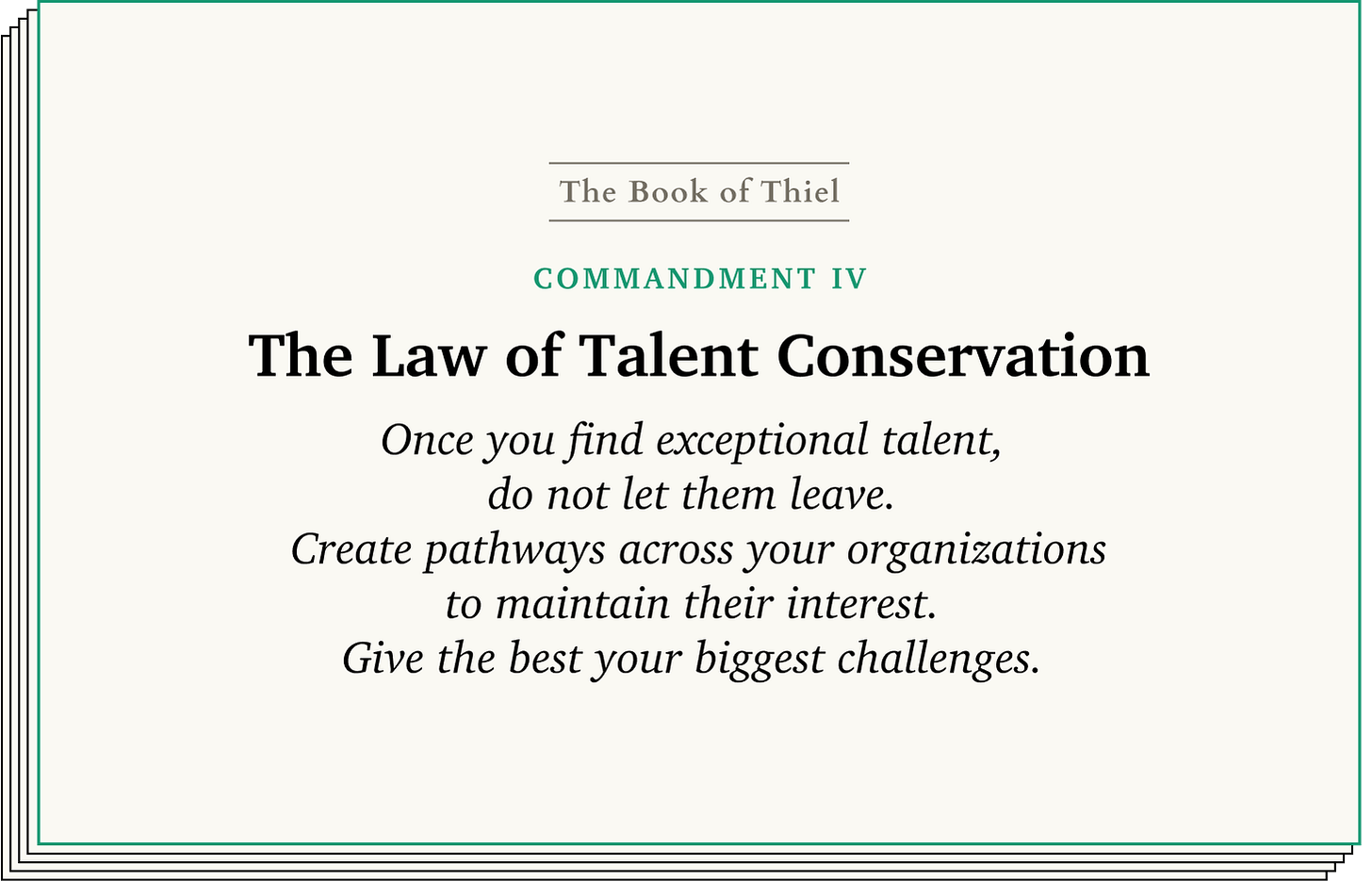

Looking at the full span of Thiel’s financial diaspora, it’s hard not to ask oneself what the point of it all is. Why bother to co-found multiple investment firms rather than unite several strategies under a single roof? Why shift employees from one organization to another?

Two reasons stand out.

First, more than almost anyone else, Thiel understands the importance of conserving talent. Once he decides someone meets his high bar, once he decides you are special, he is uncommonly proactive in ensuring that person remains in his orbit. Like a sports agent, he seems to understand what each “client” needs to further their career and deliver fulfillment, and then searches for it within his direct network. If an investor wants to experience operational life, they should join Palantir or Anduril; if an operator wants to learn how investors think, they can take a stint at Clarium or Mithril or Founders Fund; if someone is ready to start a firm of their own, why not do it with his backing?

By doing so, Thiel effectively captures part of the upside of a talented person’s entire career (or at least much more of it), reaping the benefits as they evolve from superstar operator to deft investor to founder to fund manager. Not everyone gets this support, nor do those chosen keep it if they fail to perform, but Thiel is unusually creative in hanging on to talent.

Another motivating factor may be Thiel’s sheer curiosity. He is incapable of doing one thing at a time, of staging his ambition. Always, he has at least two serious ventures running: at Thiel International, he moonlit as a founder; at PayPal, he moonlit as an investor; after PayPal, he founded a business, ran a hedge fund, and spun up a venture firm, all at the same time. By running multiple experiments simultaneously, Thiel forces each organization to jockey for his attention and capital, to prove one is more important than the other. It is, in a sense, a kind of hedging: Macro investing might seem like the best use of my time and talents today, but perhaps seed-stage venture will be tomorrow. By keeping talent in the system, Thiel gives himself the ability to run these experiments more effectively.

By the early 2010s, Founders Fund was about to become Thiel’s primary focus, powered by a Clarium refugee.

You’ll start on Monday

At the 2005 annual summit for Wesco Financial, the late Charlie Munger shared his views on investment banking and money management.

“It’s my guess that something like 5% of GDP goes to money management and its attendant friction,” Munger said. “Worst of all, the people doing this are among the best and the brightest. Hundreds and thousands of engineers, etc. are going into hedge funds and investment banking. That is not an intelligent allocation of the brainpower of the civilization.”

Had Lauren Gross been in the audience, she would have agreed. That same year, the Stanford economics graduate had taken an analyst position in Citi’s investment banking practice and found it stultifying. “I defaulted into it based on a general enjoyment of math but I wasn’t particularly blown away by it,” Gross recalled.

Still, Gross struggled to imagine what she would do instead. As far as she understood at the time, the only viable options for someone like her were to choose between banking, consulting, and perhaps a job at Google. The last of those options held little intrigue for Gross, despite her time in Palo Alto. “Unlike all of my partners that were building rockets out of their garages growing up, I was never particularly passionate about technology. I’m still not,” she said. Instead, Gross was motivated by people. “I’ve always been attracted to people that are uniquely bright. My favorite subject was always the teacher.”

Halfway through the two-year analyst program, Gross met the kind of uniquely brilliant person she’d hoped to find at Citi.

The introduction came via her friend and old college roommate, Dan Fink. “He was doing a hodgepodge of different projects for Peter,” Gross recalled. “He was connected to him because Peter stayed very connected to Stanford.” As part of Thiel’s orbit, Fink was invited to a cocktail party hosted on his rooftop overlooking San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts.

Gross knew a little about Thiel through Fink, but not much. “I knew he was a somewhat rich, somewhat important person, but I had no appreciation for his story,” she said. That was for the best. No sooner had she been introduced and asked a few preliminary questions than Gross launched into a tirade about investment banking. “I went on this long rant of how silly and mundane it was. It was drawing reasonably strong talent, but it was all about competing with the herd; modeling companies without understanding why.” Had Gross known the impressive particulars of Thiel’s resume, she might have had the urge to soften her frustration. “I’m not sure I would have had the boldness.”

Without knowing it, her tirade was tailor-made for Thiel. There was little that aggravated him more than talent sacrificed on the altar of careerism. “Why don’t you come in for an interview?” Thiel suggested.

A week later, Gross showed up at 1 Letterman Drive, Clarium’s office. Thiel got right to the point, offering her a job in investor relations (IR). “I remember saying, ‘Why do you think I would be good at that? ‘Why would I be good at IR and fundraising when I’ve literally never done and never expressed any interest in it?’” Gross said.

Thiel didn’t need a schmoozer, he explained. He needed someone sharp, sophisticated, and economically educated enough to tell Clarium’s macro story, in detail, so that he didn’t have to. He would later put the significance of the role in even starker terms: “He said to me, ‘Your bar for success is if I never have to take a fundraising meeting.’ The autonomy and depth with which he saw the role was different than I’d anticipated.”

Though Gross had majored in economics and seen the inside of Citigroup, she knew very little about Clarium’s world. That didn’t seem to faze the man sitting across from her. As he’d demonstrated at PayPal, Thiel hired for talent, not experience. “I learned really quickly that Peter just takes bets on young people, well ahead of their talent being proven,” Gross said. “I mean, when I started I wouldn’t have been able to define what a hedge fund was. Genuinely. But he just throws people into the deep end and lets them sink or swim.”

Despite Thiel’s assurances, Gross wasn’t ready to commit on the spot. “The amusing part of the story is my naivete. I said, ‘Great, well, I’d love to work for you, but I’m in this two-year investment banking program. I’m someone who’s firm in my commitments, so I have a year left.’

Thiel responded flatly, “If you like the job, you’ll start on Monday.”

Gross did. It was the beginning of a critical partnership between the pair, spanning two organizations and nearly 20 years. Though many other members of Thiel’s circle attract greater attention, few have been as essential to his continued success as the person who would become Founders Fund’s Chief Operating Officer.

But Clarium came first — a four-year whirlwind exposing Gross to the madness of the markets. Clarium’s seesawing fortunes fomented a pressurized environment and forced rapid learning. “I’m so deeply grateful that I was there through a financial crisis,” Gross said. “That’s an odd thing to say and perhaps not what Peter would want me to say, but it was a crash course in the job. You get asked infinitely more questions when things go wrong. You’re really pushed on the details: Why that trade? Why that size? Why that timing? Even if people don’t like the answers, you have to be able to nail them. I got substantially better at that during the back half of 2008.”

As Clarium teetered, Thiel surveyed the capital landscape with his quintessential sangfroid. If hedge funds were no longer the optimal way to capitalize on his skill set, what should he turn his attentions to instead? In 2010, he shared his view of the coming decade with Gross. “At so many points in my career, Peter has called these macro moments for me,” Gross recounted. “He approached me and said, ‘The next decade is going to be about venture capital. Companies are going to be staying private longer, and more of that value is going to be captured on the private side.’ It wasn’t him necessarily saying, ‘Hedge funds are over,’ but it sort of was.”

Thiel told Gross about the venture fund he’d been running on the side. Founders Fund was off to a good start, he explained, but it had minimal brand presence and needed to be bigger to capture the opportunity he expected to materialize. How much bigger? Within the next few years, Thiel wanted to raise a billion-dollar fund, he told her. “It was outlandish,” Gross said, “No one had a billion-dollar fund at the time.” There had been growth equity vintages that exceeded that benchmark, of course, but mega-vehicles had yet to come to traditional venture. Thiel wanted Gross to become Founders Fund’s lead fundraiser.

“I wanted to keep working for Peter, and I trusted his macro calls implicitly,” Gross recalled. “He placed someone I worked side by side with [at Clarium] at Palantir; I honestly would have gone there if he’d told me to.”

Gross accepted the offer, though she did so once more with characteristic circumspection, explaining that she’d love to meet the Founders Fund team and make a gradual transition. Once more, Thiel cut to the chase: “I’d like you to start on Monday.”