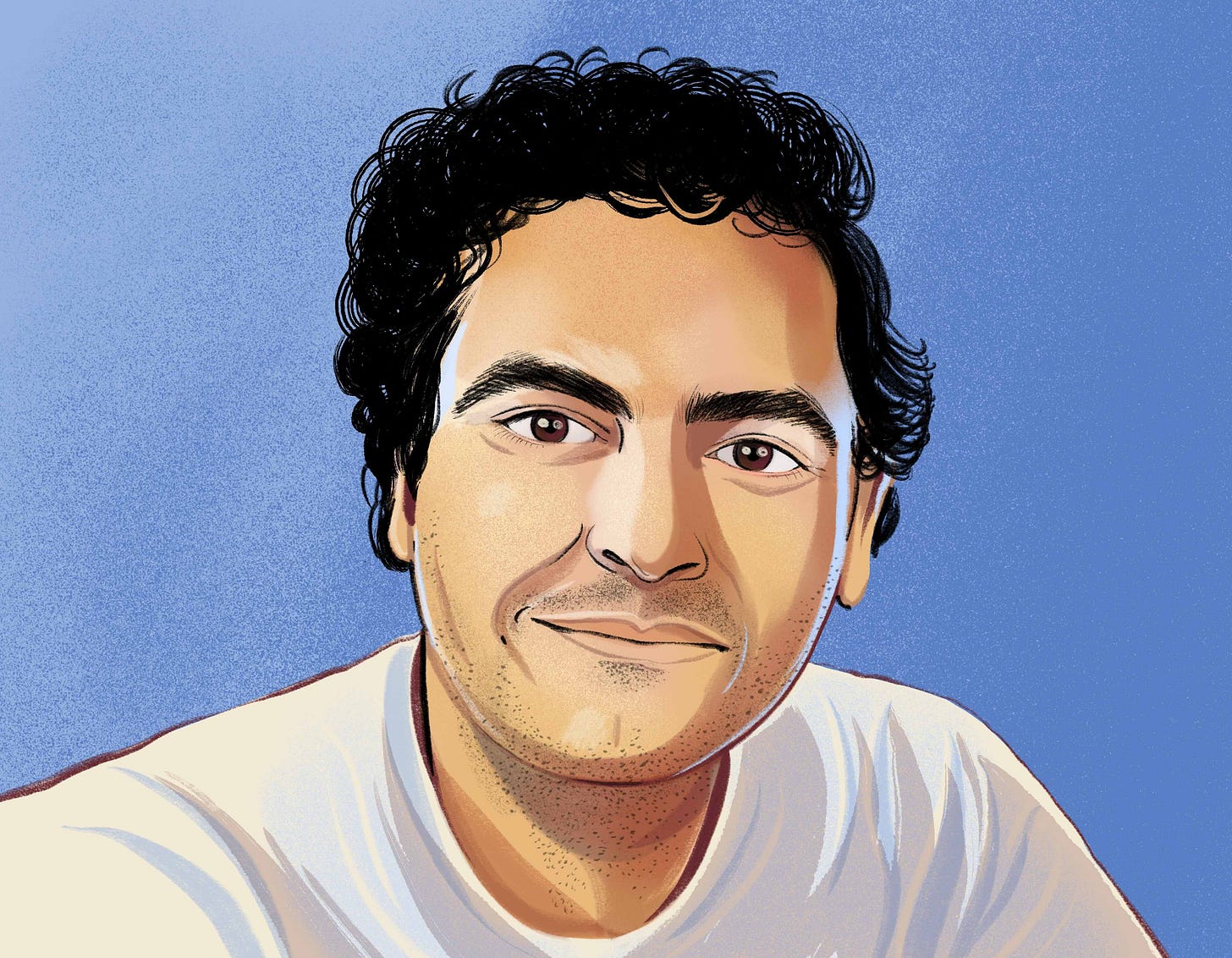

Modern Meditations: Immad Akhund

Mercury’s CEO on Genghis Khan, the limits of growth, and the secrets of excellence.

Friends,

How often do you think about the Mongolian Empire?

For Mercury CEO, Immad Akhund, the answer seems to be “surprisingly often.” For our final interview of the year, I asked the founder of one of my very favorite products to share his latest obsessions, contrarian opinions, and favorite reads.

As well as outlining the h…