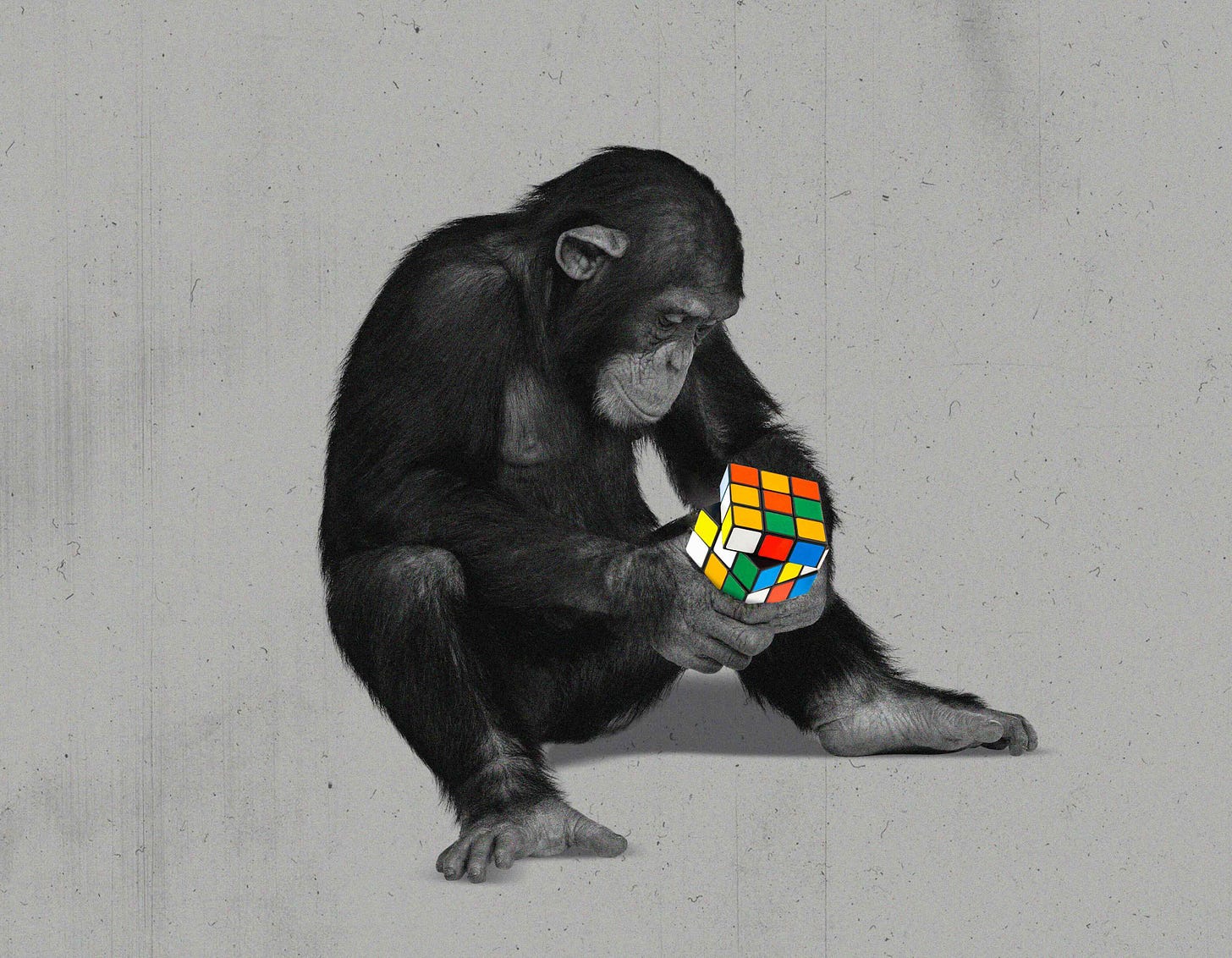

Lesser Apes

As AI gets smarter, will we get dumber?

“I think your Substack contains simply the best writings about venture out there. You provide a kind of storytelling and thoroughness that no one else does. Thanks :)” — David, a paying member

A species’ intelligence does not always increase. Many parasites have evolved to become simpler than their ancestors, shedding neural …