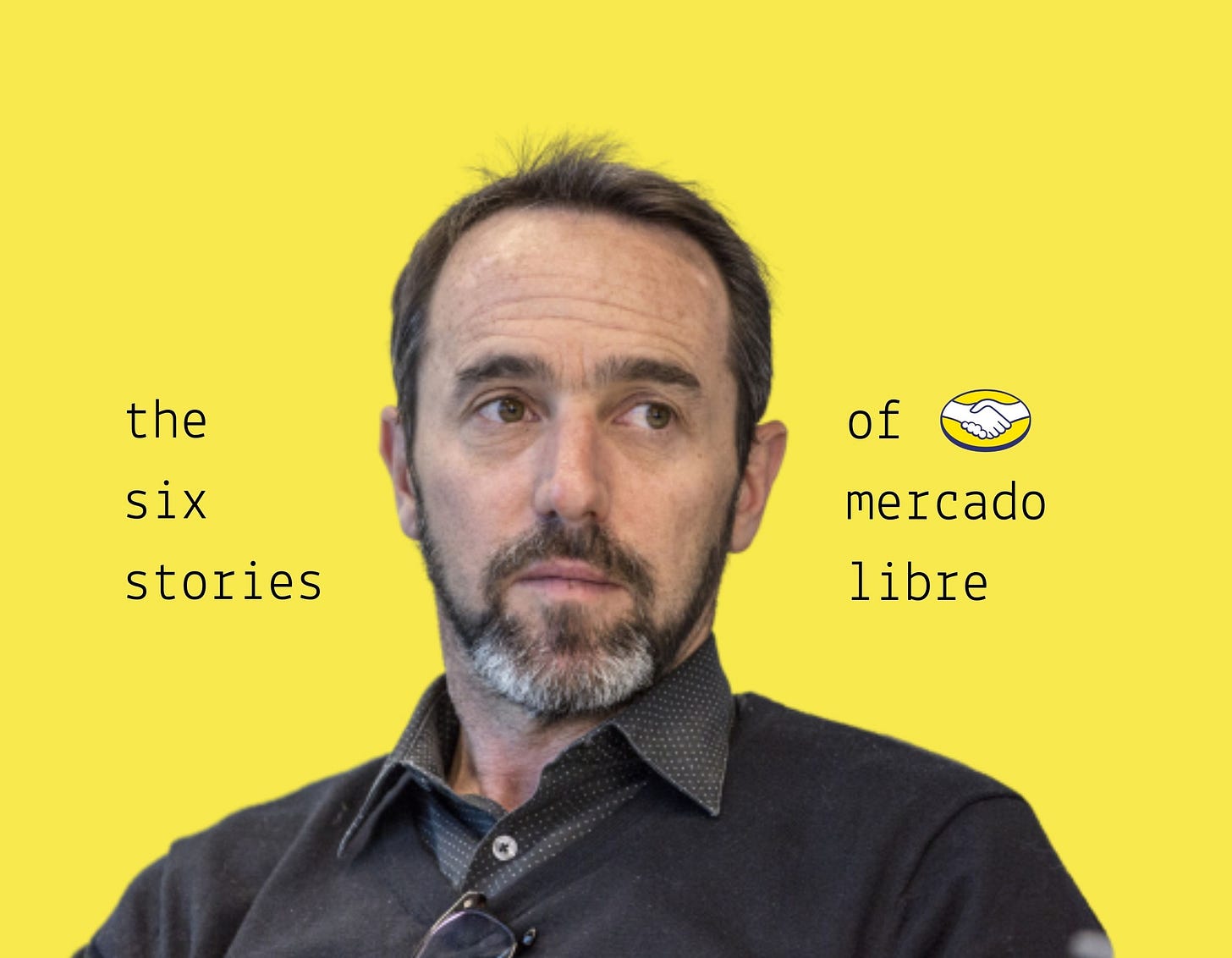

The Six Stories of Mercado Libre

Latin America's largest e-commerce company is a Borgesian perplexity.

I would like to tell you six stories.

None are mine.

One belongs to Marcos Galperin. The other five, Jorge Luis Borges.

Perhaps one of these names means something to you; perhaps both; perhaps neither. Marcos Galperin is a businessman from Buenos Aires who is alive. Jorge Luis Borges is a writer from the same city who is dead.

(It is theoretically possi…