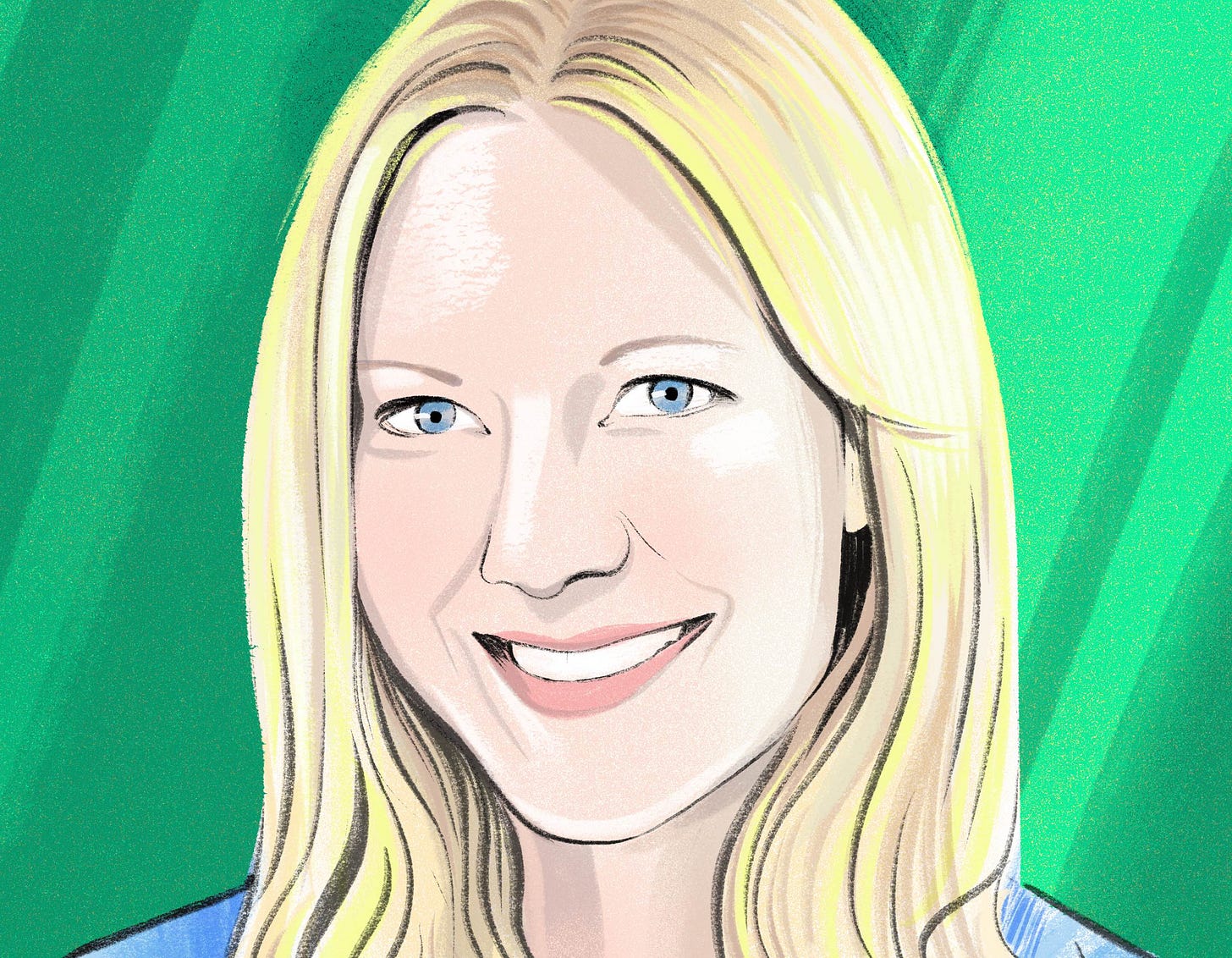

Modern Meditations: Katherine Boyle

The Andreessen Horowitz GP on American Dynamism, seriousness, population collapse, and memetic power.

Brought to you by Composer

Discover Composer - the investment app that revolutionizes the way you grow your wealth with data-driven logic. Launched in 2020, Composer’s algorithmic trading platform has already guided over 40,000 users in managing hundreds of millions of dollars in trades.

Exciting news: Composer now integrate…