Consider the Eel

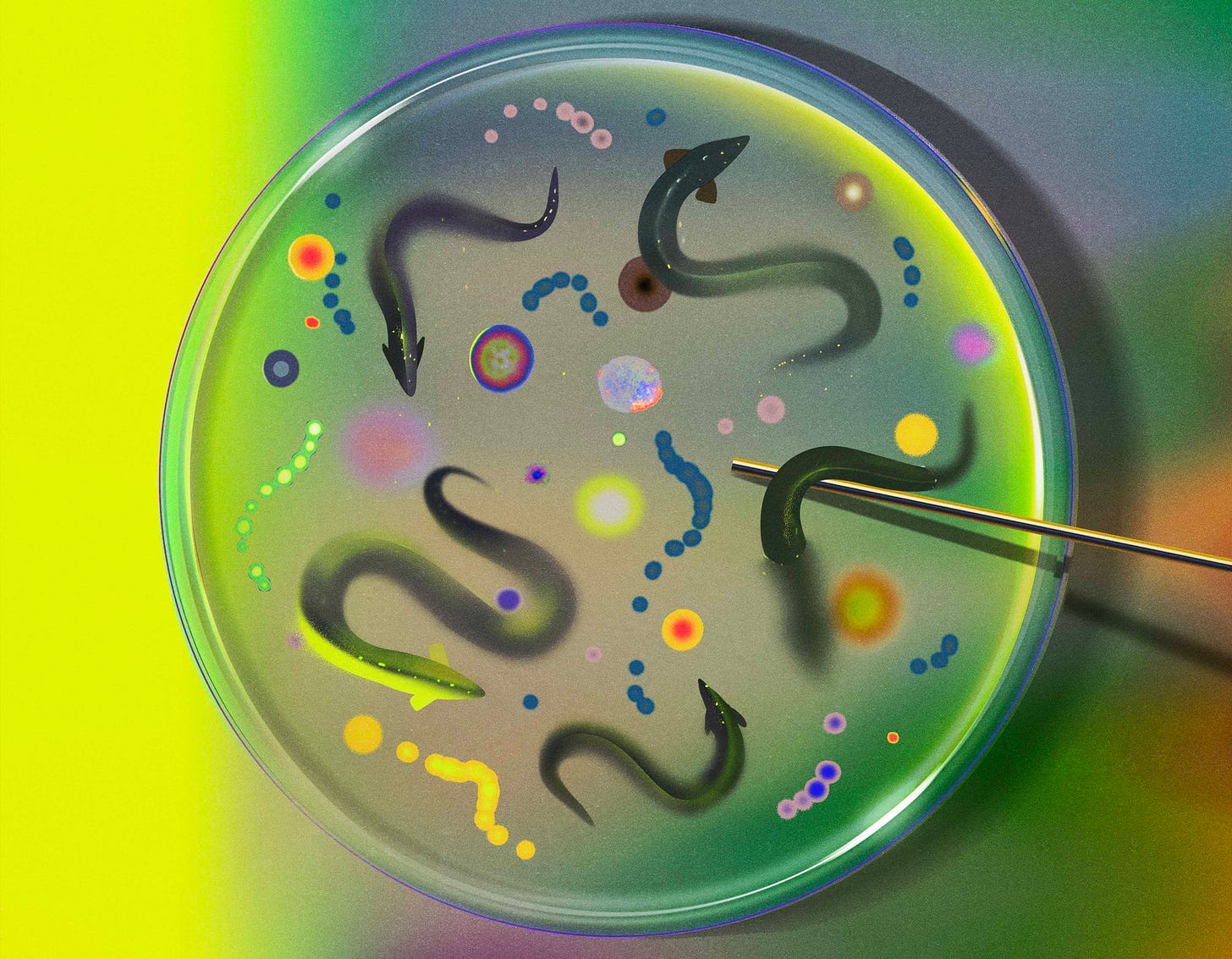

Inside the curious and potentially lucrative quest to grow eels in a laboratory.

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about the quest to cultivate edible eels in labs.

The real eel. You have seen an eel or at least a picture of one, but there’s a good chance you don’t know the real eel. These are some of Earth’s strang…